I was never very good at conforming. I was a weird kid. I liked to read fantasy stories and comic books and was a geek before it was trendy. I didn’t care very much about clothes or how I looked. Growing up, I had a few very close friends, and spent most of my time in school ignoring the people who teased me. I didn’t fit in there and I never would.

I first heard alternative music when I was 12 years old. My older cousins were staying with us, and one of them was in a punk band. I spent the summer between 7th and 8th grade listening to Nirvana, Alice in Chains and Pearl Jam. This gateway drug led to the large scale consumption of metal, hardcore and punk and by 8th grade, I was wearing plaid skirts with ripped tights and combat boots. The music made me feel understood. It was a role I had been waiting to assume my entire life.

I went to high school equipped with an arsenal of vulgar music and a bad attitude that carried me through college. I went to countless shows in shady, filthy venues and listened to the Misfits with the volume up in the lab. By the time I finished school, my hair had been black, purple, blue, pink and red, and I had accumulated a dozen piercings. I wore punk rock like armor; it was easy to retreat into loud, angry music.

Then I got older and I grew up and sold out in the way we all do. I had various jobs and wore business clothes, went to conferences and dropped my (very thick, Irish working class) Boston accent. I signed leases and bought a car. I did charity work. And I got sick.

Being sick makes you vulnerable in this long-term, uncomfortable way that I can’t compare to anything else. It makes your world unstable and therefore you are unstable in the world. It’s hard to be prepared when you don’t know what’s going to happen. And when it happens fast, it’s even worse.

I was feeling pretty incapable the day that I was told I would never get my hearing back. The person who told me was a well-known doctor at a world famous hospital. He was an excellent researcher and had an awful bedside manner. Without even looking up, he told me that I should learn to sign. When I got upset, he shushed me. (Pro-tip: Don’t ever shush me.) He told me that he had patients with Meniere’s disease who couldn’t stand up without falling down and who would gladly be deaf in exchange for equilibrium. He told me that there were patients in the hospital with cancer who were losing their hair. Then he told me that I should be grateful that it wasn’t worse.

That was when I felt it. It was the same feeling I got when I was 12 years old and first heard the Ramones. Punk rock. I was tired of doctors walking all over me and I was tired of crying. And this doctor was going to be sorry.

I stood up and didn’t move for a solid twenty seconds. I wasn’t sure what I was going to do. The doctor turned and looked at me. I walked past him, shut the door and sat back down.

“You don’t know me. You don’t know anything about me. And you don’t know anything about my life.” This swell of anger at the establishment was rising inside me. “You think I should be grateful for going deaf? You think I should just get in line behind all those sicker people because since my hearing loss isn’t as bad as cancer, you don’t give a shit? I don’t fucking think so. If you think this is an acceptable way to treat people, then I’m sure you won’t mind defending yourself to the head of your department and Chief of Medicine, because I am writing a letter and you had better fucking believe they are getting copies. I’ll call and make an appointment with someone who gives a shit that I’m losing my hearing. I don’t ever want to see you again. If you see me, don’t talk to me. You fucking suck.” I stormed out, in that really satisfying way where you can hear your own soundtrack blaring in your head.

I wrote my letters and got a few very frantic phone calls from the hospital. They scheduled me appointments with other specialists and assured me I would never have to see this asshat again. And I never did.

The next few years were exhausting and frustrating and sad, and maybe I was belligerent, but I wasn’t a doormat. I wasn’t afraid of them anymore. I got my punk rock back.

There are some days when I think that my illness has defined me more than anything else. But if you look closely, that’s not true. More than anything else, more than a loyal friend, more than a know-it-all, more than a scientist, I am a punk. I was born with a problem with authority and I’m not afraid of a fight. Every cell in my body lives for rebellion. It is the heavy bass undercurrent of my every action. Every time I argue with a doctor or refuse to accept substandard care, Black Flag is playing in my head. I have punk rock in my soul, and more than anything else, it armed me for this ongoing struggle. It saves me over and over.

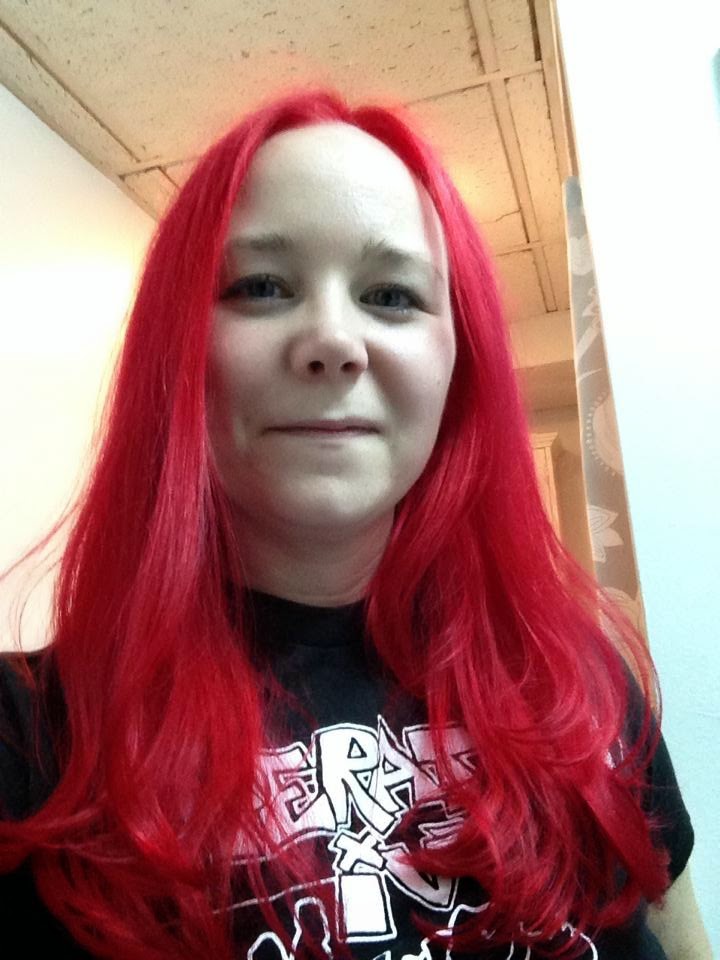

Last fall, when I started getting much sicker much faster and I wasn’t really feeling up to the challenge, I called an old friend and she dyed my hair bright red for me. I went home and put on my Operation Ivy shirt and blasted the Pogues and Bikini Kill. And I felt braver and ballsier and ready to not take shit from anybody.