If you have mast cell disease, then your life has the possibility of being turned inside out in a matter of seconds. The last time I anaphylaxed, I was sitting on my couch at home after a very pleasant day. I had to call 911, use epi, and spend five days in the hospital because I kept anaphylaxing. So with basically five minutes of notice, I had to leave my house for a week.

I am a strong advocate of having a “go bag” like pregnant women pack close to their due date. That way you can grab it and take it with you. If you’re not home, you can have someone go get it for you and it’s already packed. That way you can be sure you have all the important things you need.

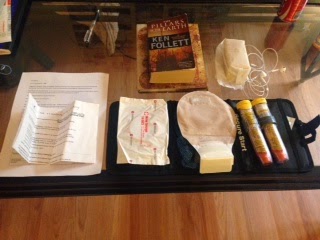

So what should your “go bag” have in it? This is what mine has:

Toiletries. A lot of us are reactive so we need specific products. I pack a toothbrush, toothpaste, face wash, body wash, deoderant, shampoo, lotion, Rocket Shower, hair brush, elastics, pins, tweezers, nail clippers, razor and razor blades, my spare glasses and my mouthguard. Rocket Shower is a spray that you spray onto your skin and then wipe off with a towel if you’re not able to shower. It’s moisturizing and it makes you feel clean.

Clothes. I always feel better in actual clothes. I pack a couple of changes of pajama type clothes, like pajama pants, tank tops and a hoodie for when it gets chilly at night. Tank tops are good because they give easy access for EKG/heart monitor leads as well as central/IV lines. Make sure your sweater/hoodie is loose so it doesn’t compress the lines or the infusion pump will think it’s occluded and beep incessantly. I find that zip up sweatshirts are better than pull overs because you get less things tangled.

Medication. I know this seems antithetical, but hospitals don’t always have the meds you take regularly. This is particularly important for mast cell kids like me because we don’t always tolerate inactive ingredients in medications, so switching brands can be dangerous for us. If you have over-the-counter meds that you take regularly, or meds that you know the hospital is unlikely to have, bring them with you. Also, things like nasal sprays and inhalers are good to bring with you. I bring ranitidine (my hospital stocks famotidine), fluticasone nasal spray and ketotifen.

Chargers. Because it’s 2014 and we can’t live without our phones.

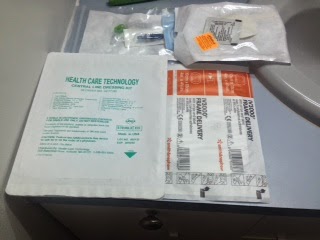

Specialized medical supplies. I have a colostomy, and products for ostomies are not really interchangeable. I also have a PICC line. Pack at least a week’s worth of supplies. I pack them in a little black pack, which also has antiseptic wipes and adhesive remover wipes that are safe for me. If the hospital has supplies that you can use, great. If not, they’re going to use whatever they have, and that might not be safe for you.

Safe snacks. If you get there at night, you’re not going to get food. If you eat low histamine or have a lot of food triggers, you may not have a lot of options. Put a few nonperishable things in the bag. (I have saltines and peanut butter.)

Head phones. So you can watch movies or listen to your music on your phone or laptop.

Journal/notebook. I write every day. It’s also good to have on hand so you can take notes while talking to your doctors, or make notes about things you want to ask.

Book. Hospitals are boring. Bring some entertainment.

Paperwork. This is important. You should have a “greatest hits” sheet on you all the time. Mine has my diagnoses and relevant procedures, indicates high risk for anaphylaxis, states emergency protocol for anaphylaxis/trauma, indicates central line, has an UP TO DATE medication list including IV meds, and has a list of emergency contacts as well as physicians to be contacted in case of emergency, with phone numbers. I also always have the Mastocytosis Society Emergency Protocol on me. At home, I keep copies of these two things on my fridge as well.

Epipens. Bring your epipens. Yes, they will almost certainly administer it to you at the hospital, but if you’re somewhere unfamiliar, with non-mast cell aware providers, it’s best to be safe.

Dog. Bring your dog to keep you company. This is Harry P. I bring him in my backpack.

And bring your purse/wallet so you have your ID, insurance cards and money. I also bring my laptop and cord so I can work.

Other things:

You should have a health care proxy, and you should know where it is. If you are regularly seen at a hospital, it should be on file there. Your proxy should have a copy.

If your condition is advanced, consider an advanced healthcare directive.

Contact your local EMS provider and ask if you can stop by and teach them about mast cell disease. My local ambulance company and fire department both have copies of my emergency protocol, so when they responded a couple of weeks ago, they knew exactly what to do. Saves time and makes you feel safe.

You should have a medic alert bracelet. If you anaphylax suddenly, you might not have time to tell someone what’s wrong.

If you have involved responsibilities, like a special diet for a pet, write them down and file them somewhere.

Write out a bill-pay schedule with typical amounts and note how they are paid (automatic withdrawal, check, etc.) In the short term, this is not a big deal. If you’re in a coma for a month, it’s crucial to not waking up to a disaster.

If your health is deteriorating and you are single (like me), I strongly advocate having either a joint account with someone you trust, or having your account in trust for someone. This allows them access to your account if anything happens to you. This is for the same reason as the bill-pay schedule: it allows you to not emerge from a health crisis and transition to a huge mess.

Have important papers organized and filed. Make sure you tell people close to you where these things are. This should include copies of your health care proxy, advanced directive, life insurance, disability policies, insurance paperwork, things like that.

I know this stuff is not fun to think about, but if you ever need it, you’ll be glad you did it, and if you don’t need it, it will make you feel better to be prepared.