The MastAttack 107: The Layperson’s Guide to Understanding Mast Cell Diseases, Part 63

77. Can you have anaphylaxis with high blood pressure?

- Yes.

- The misconception that a person with high blood pressure cannot be experiencing anaphylaxis is enduring and dangerous.

- Author’s note: Thanks to the intrepid reader who caught a big typo right here. When I published the post, it said, “The misconception that a person with high blood pressure can be experiencing anaphylaxis is enduring and dangerous.” This is a whopper mistake. It should say, “The misconception that a person with high blood pressure canNOT be experiencing anaphylaxis is enduring and dangerous.” You CAN have high blood pressure and anaphylaxis at the same time. Thanks again!

- Lots of providers (and patients) think that high blood pressure rules out anaphylaxis. This is not true.

- This misunderstanding comes from confusing two closely related but distinct concepts: anaphylaxis and anaphylactic shock.

- Anaphylaxis is a severe allergic reaction affecting multiple organ systems.

- Anaphylactic shock is when anaphylaxis causes such poor blood circulation that the heart cannot pump out enough blood to the body.

- Anaphylactic shock is a form of circulatory shock, which means exactly what I just described: oxygenated blood is not being pumped out of the heart and through the blood vessels to the tissues that need it.

- Anaphylactic shock is defined as blood pressure 30% below the patient’s baseline or a systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg. The systolic blood pressure is the top number when you get your blood pressure checked. If that top number is below 90 mm Hg, and that is the result of anaphylaxis, you are in anaphylactic shock.

- Anaphylactic shock is the most serious potential complication of anaphylaxis. Anaphylactic shock happens when the chemicals released by mast cells cause a lot of the fluid in the bloodstream to “fall out” of the bloodstream and get stuck in the tissues.

- When this happens, that fluid loss causes the blood pressure to drop. In response, the heart beats faster to try and use the blood it still has left to get oxygen to the body. However, at a certain point, even beating really fast is not enough to get enough blood to the tissues. At this point, shock sets in.

- Anaphylactic shock occurs specifically as a result of low blood pressure. Because of this, providers strongly associate low blood pressure with anaphylaxis. They may not realize that while a person with high blood pressure cannot be having anaphylactic shock, they can be having anaphylaxis.

- Part of the confusion is that anaphylaxis has been defined lots of different ways by many different groups. I have written a very detailed post about this (see the link below). Even today, exactly what constitutes anaphylaxis not agreed upon by everybody.

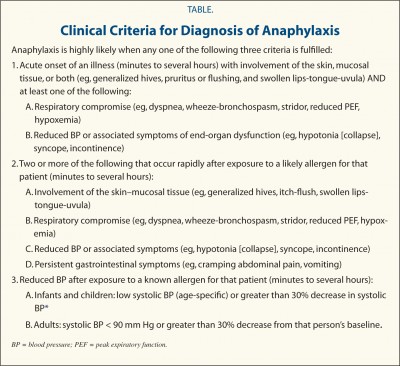

- The most widely used criteria in the US are the criteria published in 2006 by the World Allergy Organization journal. These criteria explicitly state that a person does not need to have low blood pressure to be having anaphylaxis. A person can meet these criteria based upon a variety of combinations of symptom and vital signs that do not include low blood pressure.

For additional information, please visit the following posts:

The definition of anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis and mast cell reactions

The MastAttack 107: The Layperson’s Guide to Understanding Mast Cell Diseases, Part 49